| All of us have a personal superpower. It may be a skill, like

baking or singing. It may be a social knack, like getting strangers to trust us instinctively. It may be an

intellectual ability. My own personal superpower is making connections. I compare things. I zero in on how they are alike and how they are different. I put Tab A in Slot A and Tab B in Slot B and keep going, without necessarily knowing where I am headed, until I find myself holding a fully-rigged cardboard pirate ship. Or a theory of human history. When I began my venture into historical theory, all I knew was that I had identifed what seemed to be a regular cycle of alternations between "creative" periods, characterized by rapid evolution in literature, art, technology, and politics, and "static" periods, which might have their own high achievements but lacked that kind of sweeping change. At that point I started comparing, contrasting, and drawing ever-finer distinctions. And as I did so, more and more pieces fell into place. One of the first things I realized was that both creative and static periods could be divided into sub-periods that seemed to follow one another every bit as regularly as the primary alternation between creative and static. The creative period was simple, consisting of two subperiods of roughly equal length. The first of these, which I came to think of as "Classical," was characterized by a self-confident and well-integrated approach to issues, vigorous and effective problem-solving, and a quality of serenity and balance in its artistic creations. The second subperiod, which I thought of as "Romantic," was a direct continuation and expansion of the first, but was marked by a less deliberate and more emotional approach, the emergence of powerful internal contradictions, and a visionary and mystical quality that was often blended with eccentricity or even outright perversity. I initially derived this distinction from the art and literature of the late 18th and early 19th centuries -- a time when the classical rationality and restraint which had been dominant from roughly 1760 to 1785 gave way to far more romantic, imaginative, and often angst-filled forms of expression -- but they seemed to apply equally well to more recent creative periods. For example, a very similar progression could be traced out between the middle 1860's and the end of the 1890's. In art, that period started with the daylight clarity of Impressionism and ended with the writhing forms of Art Nouveau and nightmarish works like Edvard Munch's "The Scream." In imaginative literature, it began with the vigorous juvenile tales of invention and exploration written by Jules Verne and his dime novel imitators and concluded with stories of supernatural horror, like Bram Stoker's Dracula, and the fevered and apocalyptic imaginings of H.G. Wells. The same kind of transition could be seen as dividing the popular culture of the 1930's from that of the 1940's. Modern science fiction, for example, had enthusiastically investigated its basic themes and settings during the course of the 30's, including the technological near future, the exploration of outer space, galactic civilizations, time travel paradoxes, and parallel universes. But when the United States entered World War II in December 1941, the mood abruptly shifted. Many leading edge SF writers turned to military service or war work, and the readers themselves began to show a greater fondness for romantic escapism or wacky surrealism than for plausible future histories. Even after the war came to a successful conclusion, it proved impossible to recapture that earlier sense of infinite future possibility, so that late 40's SF was split between grim tales of nuclear devastation on one hand and hyper-romantic science fantasies on the other. ***** In contrast with the simple one-two progression of the creative period, the static period seemed far more complicated, with a jagged and discordant rhythm that could be roughly broken into three sub-phases. The central phase of any static period was always marked by the emergence of new ideas and new centers of political and cultural influence and climaxed in a relatively brief moment of intense artistic ambition and accomplishment. However this peak period was regularly both preceded and followed by phases of cultural decline and social disintegration. For example, the wave of stylistic experimentations and cultural rephrasings in the middle and late 1960's -- which encompassed science fiction, rock music, film, and other areas of popular culture -- had immediately succeeded a particularly stagnant phase, which began in the middle 1950's and was chiefly notable for its reduction of the central themes of the previous creative period to sterile cliches. At the end of the 1960's, however, the hippie and anti-war countercultures had sunk into a morass of violence and fragmentation, and by 1972-73 the last remnants of hippie idealism had largely given way to the self-conscious decadence of glam rock and X-rated movies. During the early 20th century static period, the years from about 1912 to 1921 could easily be recognized as the same kind of isolated artistic peak, which featured not only a brief and hectic flowering of scientific romance, but also a very 60's-like melange of bohemianism, radical politics, artistic experimentation, subversive music, and daring experiments in lifestyle. Like the 1960's, the 1910's had followed a decade notable for its complacency and imaginative retreat. And like the early 1970's, the 1920's had been a period of scandal, disillusionment, and decadence -- a time when idealism and utopian dreams collapsed and surrealism, anarchic comedy, and supernatural horror became the most successful forms of artistic expression. The early 19th century static period offered less in the way of imaginative fiction to help illuminate its development, but it was still apparent that there had been a brief spurt of influential proto-SF stories by Edgar Allan Poe and his contemporaries in the 1830's and 1840's, flanked by far less productive periods both before and after. What's more, those peak years-- like the 1960's and the 1910's -- had coincided with general impulses in the culture at large towards bohemianism and artistic rebellion. (Indeed, the very term "bohemianism" was first used in the 1840's.) The early 18th century static period was far more unfamiliar territory for me, but a little digging in literary and artistic histories suggested that there had been a distinct cultural peak around 1730-50, which had been preceded by a couple of decades of social complacency and artistic insipidness and succeeded by some 10 or 15 years of courtly decadence and frivolity. ***** In the course of working out these various distinctions and parallels, I had begun designating the five phases by the letters from A to E -- partly because I hadn't managed to come up with adequate descriptive terms and partly just for the sake of simplicity. The static period flowering, which seemed to set the entire sequence in motion, I called the A period. The succeeding phase of decadence was the B period. The Classical and Romantic phases were the C and D periods, and the final cultural decline was the E period. At this point, I was not altogether sure if what I was seeing was real or the result of a misguided attempt to impose structure and order on a random assemblage of historical events. However, I did take encouragement from the fact that I seemed to be able to lay out certain expectations in advance, dive into periods with which I was not previously familiar, and find those expectations confirmed. The next test of my theory, then, would be to discover whether the complete A-to-E sequence would still present itself in even more foreign territory. In the course of my initial work on organic and geometrical periods of fashion, I had tentatively pegged the 15th century Italian Renaissance as the heart of a particularly spectacular static period and the 17th century Baroque as the succeeding creative period.. Returning now to the Renaissance, this time with a pile of art books at my elbow, I quickly found that, just like more recent A periods, it had been preceded by an extreme cultural wasteland in the late 1300's and followed by a period of decadence -- characterized by mannerism, over-refinement, and artistic disequilibrium -- from about 1520 to 1580. So far so good. When I attempted to look back further than the Renaissance, however, it wasn't immediately clear to me just how long the static-creative alternation had existed. Rapid changes in style, together with the type of form-fitting, nipped-in women's dress that I considered the hallmark of organic fashion, had only come into being in the late Middle Ages. Was it possible that the cultural ferment of creative periods was a relatively recent development -- a true innovation in human psychology -- and that all of history prior to the 1300's had formed a single extended static period? I toyed with that notion for a little while, but I couldn't quite bring myself to believe it. For one thing, cultural and social change have always been a fact of human existence. There is no place in the world, no matter how remote or seemingly primitive, that has not undergone some degree of change over the last 10,000 years. For another, the history of ancient Greece and Rome struck me as a textbook example of the complete five-part cycle -- with the heroic era of Homer as the A period, the breakdown of the old warrior society as the succeding B period, the flowering of classical Greek culture as the C period, the centuries of Hellenistic learning between Alexander the Great and the early Roman emperors as the D period, and Rome's extended decline and fall as the concluding E period. The history of ancient Egypt was next to fall into place, with the spectacular birth of civilization climaxing in the Pyramid Age of the mid-3rd millenium BC as the A period and the collapse of the Old Kingdom into turmoil and fragmentation as the B period. The Middle Kingdom in the early 2nd millenium and the New Kingdom in the middle 2nd millenium provided the C and D periods, followed by a crashout into the dark age of the E period around 1200 BC. It seemed that, if anything, the cycles had been more dramatic in ancient times, marked by the rise and fall of entire civilizations and not merely by the inner turmoil of artists and philosophers. ***** In mapping out these equivalences, I was prepared to be satisfied with rough-and-ready approximations, because all I was really looking for at that point was a basic scaffolding into which I could plug historical and artistic details as I acquired them. I figured that if I was grossly mistaken about any of it, I would find out soon enough -- while if I was right, my schema would automatically improve as a result of working with it. However, a few intriguing conclusions had become apparent even on the basis of these tentative assignments. One was that as I pressed further back in time, the cycles became longer and longer -- expanding from decades to centuries and then to millennia. Another was that these ancient cycles seemed to line up neatly with well-defined historical eras like the Bronze Age, in the same way that more recent cycles corresponded to recognized periods like the Victorian era.  I also came to realize that there really had been an alternation

of geometrical and organic fashion in earlier times. However, it

had been more like recent changes in men's clothing -- gradual and

low-key and affecting primarily the wealthy and display-conscious -- than

like the explosive variations which have occurred in women's costume over the last 600

years. I also came to realize that there really had been an alternation

of geometrical and organic fashion in earlier times. However, it

had been more like recent changes in men's clothing -- gradual and

low-key and affecting primarily the wealthy and display-conscious -- than

like the explosive variations which have occurred in women's costume over the last 600

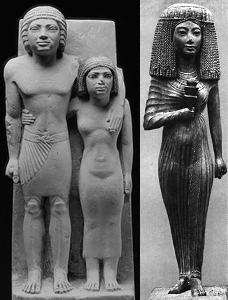

years.In the attire of Old Kingdom Egypt, for example, what appears to have been relatively heavy fabric was pulled tightly around the body, flattening the natural countours and regularizing their outlines (left). In the New Kingdom, by contrast, although the garments remained very similar in cut, the fabric was far more delicate and clung to the body in subtle pleats that emphasized the natural roundness of hips, belly, and shoulders and the narrowness of waist and ankles (right).  In

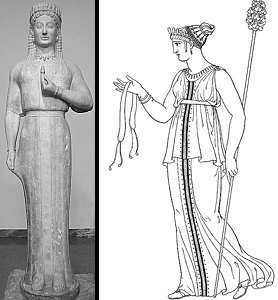

Greece, there had been a very similar transition between the stiff

lines of the late archaic period and the figure-hugging folds

and

curves of classical costume. In

Greece, there had been a very similar transition between the stiff

lines of the late archaic period and the figure-hugging folds

and

curves of classical costume.Once I had these two examples to refer to, I felt far more comfortable in concluding that the cycles had operated in essentially the same manner 2000 or 5000 years ago as they do today. The only difference I could see was that things move a lot more quickly these days, which I assumed was the result of technological advances in transportation and communication that have enabled innovations to spread far more quickly. At the time, that seemed to be the most logical conclusion -- and I was glad of the go-ahead it provided to start applying what I had learned about modern cycles to more ancient ones. But as I now revisit the work I did 35 years ago, I feel far less ready to rule out the possibility that there may have truly been a fundamental shift in perspective over the last few thousand years. In 1973, I was afraid of revealing myself as some kind of modern-Western cultural chauvinist if I even hinted that I thought people today were somehow "better" than people in the distant past. But as of 2008, it is clear that there is another alternative. What underlies the acceleration and intensification of the cycles may be neither of the two alternatives I perceived in 1973 -- superficial technological change or fundamental psychological alteration -- but rather a profound cultural evolution. Human nature has not changed noticeably over the last 10,000 years, but the way in which human beings think about themselves and their relationship to the universe has altered out of all recognition. Throughout most of history, people everywhere have perceived the world as stable and eternal. Once upon a time, back in the Dreaming, certain things might have been different -- but ever since then, life had followed the norms laid down by the First Ancestors. As it was now, so it had always been. Even when changes did happen, people quickly wrote them into the myths and believed that things that been that way forever. At a certain point, however, that sense of an eternal present became harder to maintain. Writing appeared, and with it written records -- lists of royal dynasties, accounts of conquest and empire, stories of ancient heroes set in a world that grew increasingly unfamiliar. At the same time, centuries of carefully recorded astronomical observations started making it clear that even the heavens were inconstant. The initial reaction to this dawning perception of change was to hope that it would just go away again -- that some day history would come to an apocalyptic end, and the world would once more be perfect. Until then, change could only be seen as decay -- and major changes as portents of impending doom. This kind of neurotic apprehension must have been particularly acute in Western Europe following the fall of the Roman Empire, which was accompanied by sweeping changes, most of them for the worse. But it may also have forced Europeans to come to terms with change in a way that was not necessary in more stable civilizations, like those of China and India. Whatever the cause, a revolutionary new attitude towards change appeared in Europe in the 1300's. At first it only affected frivolous things, like fashion, but by the 1600's -- following the revival of learning in the Renaissance, the discovery of America, and the new Copernican astronomy -- it was no longer possible to deny that the world was altering in unprecedented ways and with unprecedented speed. Since then, the perception of change as the primary fact of life has become universal -- thanks in part to the heavy hand of Western imperialism imposing change in even the most distant corners of the world -- and the ancient pattern of expectation has been entirely upended. As we enter the 21st century, although pockets of fear and apprehension remain, for the most part change is not only accepted but actively pursued. Constant innovation has become the ideal, seen as the sign of a healthy and vigorous society, while stability is considered a sign of backwardness and ignorance. We tend to take this reversal of all former expectatations for granted, as some sort of inevitable result of of our greater knowledge of the world. And yet this fundamental shift in attitude is really extraordinary, particularly since in most respects we are no wiser or more mature than our ancestors. How are we to make sense of such a radical transformation? One way of looking at it might be to suggest that humans were always change-bringers, though we didn't know it yet and weren't ready to to acknowledge it. But now whatever hidden transformative factor has been operating through the cycles on an unconscious level has risen to the surface of consciousness -- like a lurking intuition that we have only just managed to grasp -- and we are eagerly pursuing it for whatever further rewards it may offer. Or to put it in a slightly different way, my son suggested to me after reading the introduction and first part of this discussion that the cycles may be an example of what complexity theorists call an autocatalytic set -- that is, a process which repeats cyclically but also becomes more elaborated with every repetition. If that is so, then the cycles, which appear to have started off as an unconscious mechanism that helped to accelerate human cultural evolution, could now be turning into the means by which we all become conscious agents of that same evolution. 9/9/2008 (minor edits for clarity 11/30/08) |

Background courtesy of Eos Development |