![]()

Alexei Panshin's The Abyss of Wonder

|

| The

fortunes of the Panshin family in

Voronezh may have been at their zenith at the time my father was

born.

While he was in the process of growing up, however, they went rapidly

downhill.

The easy life to which the Russian landed aristocracy had grown accustomed was fated to come to an end after the serfdom on which it was founded was officially abolished in 1861. My grandfather was a boy not yet nine then. And although he couldn't foresee that the day would come when one of his own sons would inform him that he was "an oppressor of the masses," nevertheless he would understand and accept that it was going to be necessary for people of his class to change their ways. My grandfather prided himself on his progressive views. He might still send his favorite black stallion off to Paris to win a prestigious harness race, but he only had contempt for his two sisters who continued to live their lives as creatures of society and fashion. He believed that every man had a duty to perform responsible work and to make provision for his family through his own efforts. His chief occupation was the breeding, training and trading of horses. But even though he was successful at it, and his Orloff horses were respected, that wasn't enough to satisfy him. He didn't care to be just another horseman, heir to an outworn mode of life. The horse was not the way of the future.  A new century was coming, and he was

determined

to keep up with the times. So, as a man in his forties, he

staked

his wealth on becoming modern.

A new century was coming, and he was

determined

to keep up with the times. So, as a man in his forties, he

staked

his wealth on becoming modern.

He took his greatest bit of unearned good fortune -- Petropavlovka, his largest estate, bequeathed to him by the eccentric maiden aunt who lived there because he was the only person in her extended family who never bothered her -- and worked to see this long-neglected place transformed into a model sheep ranch. Development of the project he placed in the hands of a professional agronomist, a young graduate in the study of scientific farm management. Then, at the turn of the century, my grandfather erected a new grain mill in Voronezh, a four-story brick building filled with up-to-date equipment. His brother-in-law, who was a mechanical engineer, was in charge of its design and operation. But the changes that he was making at Petropavlovka were not happily received, and in one of the popular uprisings which followed Russia's defeat in the Russo-Japanese War, a mob of peasants ransacked and burned the buildings and made off with the sheep. The young agronomist was lucky to escape with his life wearing the dress of a peasant woman smuggled to him by his village sweetheart. He would be blamed by my grandfather for having antagonized the local people with displays of pride and arrogance. But the truth was that Mihailovka escaped suffering a similar fate only because the invading peasants became preoccupied in destroying two mechanical harvesters, the likes of which they'd never seen before, and my grandfather was given time to arrive from Voronezh with half-a-dozen troikas laden with extra bells to sound like an even greater force, and managed to scare them away. However, he would not be able to go on with his experiment in sheep farming. He had already mortgaged Petropavlovka in order to pay for building the mill, and he was overextended. If he wanted to hold onto the grain mill, then he had to let go of the estate and the sheep. So he sold whatever remained -- with the sole exception of a boulder of red granite, six feet high, six feet wide, and twelve feet long, which had been discovered there, an anomaly in the black earth. My grandfather had that dragged through the snow on a sleigh drawn by oxen to Mihailovka, where he set it in place as the centerpiece of his main flowerbed. And thereafter, he didn't keep sheep. The grain mill operated successfully for more than a decade. But then a fire broke out in the building one Sunday, the day before my father's tenth birthday. The blaze could not be contained, and the mill was lost, too. The brick shell of the gutted building continued to stand as an eyesore for more than thirty years. Eventually Dad had to be told that all he could expect as his portion was an education. What that actually turned out to mean was that he would be able to spend a difficult year living at home while he worked in a medical supply warehouse for one hot meal a day, a pound of black bread, and money that had no value, and did his best to study botany at a university displaced from Estonia to Voronezh by World War I.

|

|

The First World War, even more than the

Russo-Japanese

War, put a strain on the ability of an autocratic and repressive

Russian

government to continue to keep the restiveness of its population under

control. Riots, strikes and military insurrection escalated

into

a revolution in March 1917 that ended with the abdication of the Tsar.

This radical break with the past was widely welcomed within the country as something long overdue. But two attempts in the following months to create an effective successor government that would be more liberal and inclusive were failures. Peasants and workers wanted an end to Russia's involvement in the grinding and inconclusive war in Europe, and were hungry to see a redistribution of land and wealth. And these would become the avowed purposes of the Bolshevik revolutionaries who seized the government and major cities in a coup that fall. Three more years would pass before the issue of who ruled Russia was finally settled. The story of this struggle is that the White Army, composed of everyone from monarchists to socialists, lost the Civil War they thought they were fighting because they had too many conflicting goals in mind, whereas the ideologues who directed the Red Army were able to carry the Revolution they'd launched through to a successful conclusion because they were more unified in purpose.

|

|

During most of this period, Voronezh was

under the

control of the Reds. But in October 1919, the Red Army

withdrew from

the city to defend Moscow against the threat of a daring White Army

cavalry

offensive, and the White Army then swung around to occupy a

lightly-defended

Voronezh.

By that time, few of the Panshins' former possessions still belonged to them. Losing Mihailovka had been a foregone conclusion, but they had hoped to be able to make the transition a smooth one. Instead, the estate had been seized by a committee of peasants. Both houses were burned down, and the tree-lined alleys, orchards and park were leveled. The cattle were parceled out, and the Orloff trotters were turned into plow horses. In Voronezh, my grandfather's stables and half the Panshin home were taken over by a Red Army cavalry unit -- who then served as protectors of the family against the worst excesses of anarchy and terror in the city. But their orchard would be chopped down for firewood. And to keep themselves fed, they would have to barter away their clothing, their rugs and furniture, their silverware, even the frames from their ancestors' portraits. The disastrous way that my grandfather's ventures into sheep ranching and grain milling had turned out -- which the family would call his "reverses," as though they'd been losses at the gaming table -- may in great part have been due to his own mistakes. He wasn't prudent. Anyone who fathers thirteen children and then mortgages his assets is presuming rather heavily on continued fair weather and smooth sailing. Instead, he was impatient, and inclined to push his luck. At the same time, as someone who'd been educated at home by tutors, he was too ready to respect the authority of those more systematically knowledgeable than he. Impatient and imprudent gamblers who chase after the systems of others suffer reverses. But the calamity sweeping over him now like a tidal wave was completely beyond his power to affect. It applied to all members of his class and every owner of property. And the only way that he could ever have avoided this disaster would have been by leaving Russia as a young man and ceasing to be a Russian aristocrat of his own accord. In actual fact, however, my grandfather was sixty-five years old and completely incapable of being anything other than the man that he already was. He had no alternative but to stand by and watch while everything that his forefathers had gathered together was stripped away from him. His former progressive sympathies deserted him. All that he could do was try to comprehend the full measure of what he'd lost, savor his own bitterness, and find vindication in the reiteration of old truths.  He blamed the current social chaos on a

wayward

younger generation that had lost its proper respect for the authority

of

parents, church and state. In his impotence and anger, he

would point

to his own children as the nearest examples of this falling

away.

And they would then prove the truth of his words by attempting to evade

his tirades.

He blamed the current social chaos on a

wayward

younger generation that had lost its proper respect for the authority

of

parents, church and state. In his impotence and anger, he

would point

to his own children as the nearest examples of this falling

away.

And they would then prove the truth of his words by attempting to evade

his tirades.

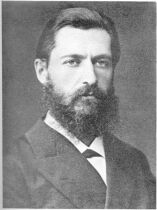

Nobody paid any attention to him now -- not even those people who in previous times would have been ready to think of him as a class enemy. When the Communist victory was finally secure, my grandparents would be allotted a single room in what had formerly been one of my grandfather's properties. And that is where he would spend the remaining years of his life. A picture of my grandfather was taken when he was in his eighties. He looks like some cross between Father Time and King Lear -- a grave old man with a high forehead, deep lines in his face, white hair and a long white beard. He wears a heavy coat and his hand rests on the head of a cane. But there is a distant look in his eyes, as though his mind is really on other things. |

|

| Back | |

Border courtesy of FDZ Graphics Bullet courtesy of Dreamcatcher Graphics |